In discussing open science, one forgets that its key concept is collaboration, which may be either accelerated or hampered by digital technologies. Collaboration in personal interactions is hard; how much harder, then, is it to collaborate across temporal, geographical, or cultural barriers? Open science can be seen as a worldwide case study on peopleware—a major source of costs, but a huge asset.

Introduction

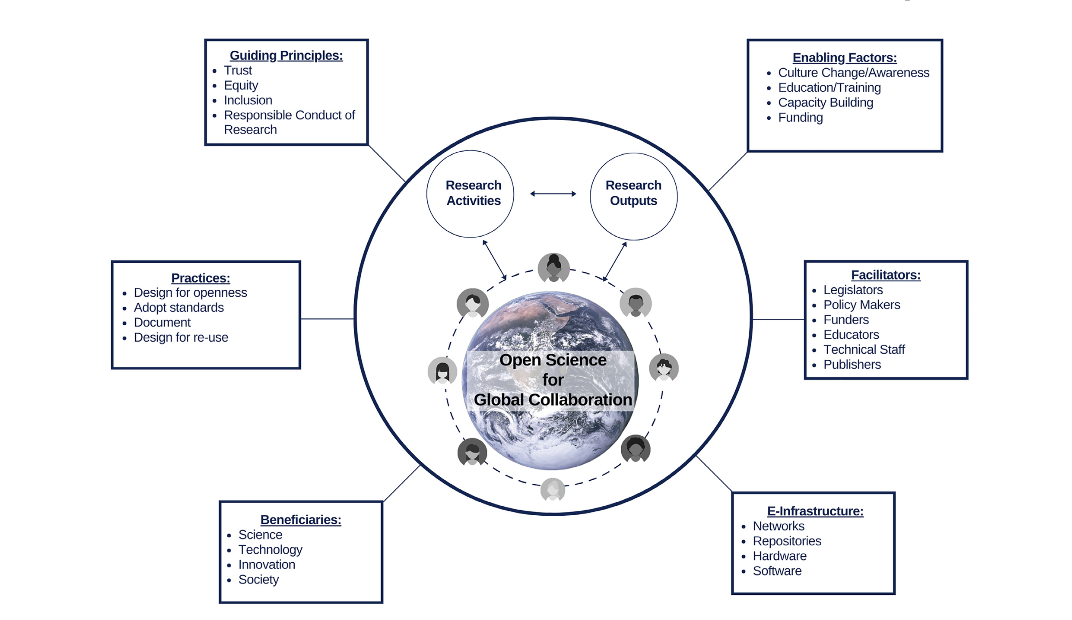

The UNESCO draft recommendation on open science, which took 3 years to prepare, with inputs from member countries and scientific societies, is the most visible worldwide political effort toward the open science movement. Though researchers recognize the value of collaboration as a means to improve or accelerate knowledge discovery, all acknowledge that there are challenges and barriers to achieve cooperation. Such challenges vary from the individual to institutions and regions, involving economic, technological, or sociocultural factors. The lack of a consensual definition also hampers implementation and compliance.

Some point out that, since open science is an enabler of “collaboration without barriers,” it actually dates back to the 17th century, having been born with the first journals and records of correspondence among scientists. This notwithstanding, the more widespread understanding is that it is associated with digitally enabled scientific collaboration, through sharing the digital objects associated with research.

This stress on the digital points out our dependence on technological enablers and the very many challenges posed by the many kinds of digital divides—social, cultural, economic, educational. This dependence has also prompted the continuous appearance of new kinds of computing infrastructures, standards, and frameworks to support open science. The associated terms “accessible,” “reproducible,” and “reusable” originated research in many fields in computer science and are key to understand this movement and the challenges it poses to information technology. “Reuse” in particular is fraught with undercurrents, since it also implies repurposing, and the fear this will produce undesirable side effects to one’s research. This is an example of the dual ways—advantage, barrier—people react to open science.

Download the full article The hidden dimension of open science: ‘‘Peopleware’’ here.